Small Publishing for the Layman

A lot of people have recently asked me to explain how the money side of publishing works. I did it for 12 years, and when I sold the company it was in the black. (Grins. I’m sorry for what happened after that, y’all.)

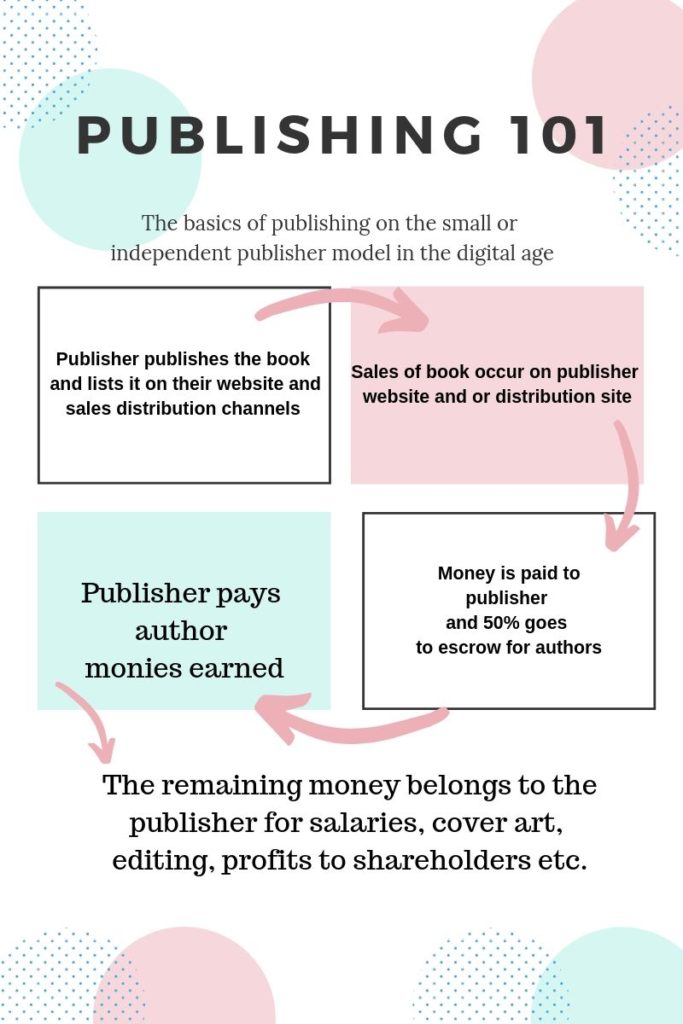

So here’s how the basic model works if the publisher pays quarterly, like we did.

The publisher takes the book, gives it edits and a cover, formats it, and lists it for sale. All of this contributes to the publisher’s operating costs, which we’ll come back to later. Once the book is ready to release, the publisher lists the book on their website (this is called direct sales) and on 3rd party distribution sites (these would be Amazon, ibooks, Kobo etc.).

Once a sale is made, the money is considered earned by both the publisher and the author. On a direct sale, the money goes immediately to the publisher’s account, whether Paypal or direct deposit. The money is then divided into two separate accounts. The general fund, which pays said operating costs, and the author escrow account. The author escrow account exists because as soon as the book is sold, that money belongs to the author, and it can’t be touched, so the safest action is to shuttle it to a separate account from the get go.

Once the quarter ends, the publisher totals up the author’s sales, figures out how much money the author receives (which can be complicated), then pays them the reported amount out of the author escrow fund. While this is considered an expense on the publisher’s taxes, it’s not considered an operating cost.

The other account, the general fund, pays artists, editors, the light bill at the office, travel expenses, etc. Everything that keeps the publisher running. Never the twain shall meet, though. The author is not a contractor. They’re a partner in the business, of sorts.

Now we’ll look at the timing of those payments.

Direct sales, those sales a publisher makes on their site, get paid at the end of the quarter they’ve been earned in. So, if the book is sold in January, February, or March, for example, then the publisher pays the author on their first quarter check, usually remanded in April or maybe May.

Distributors, on the other hand, pay on a lag. So Amazon makes a sale in January, then they pay the publisher at the end of March. Some publishers have a different deal there, and we’ll go into that too. But those payments then, would be considered second quarter on an author check. So for first quarter, ideally the check going out in April or May, the author sees their sales from January, February and March on direct sales, and from October, November and December of the year before on distributors.

With me?

Now, say Amazon doesn’t pay the publisher for December until it’s too late to pay the author. In that case, the publisher wouldn’t report that to the author, and would wait until they were in receipt of the money to put it on statements and pay it out.

This is why the escrow account is so important. Depending on when the distributor pays (like some translations companies pay only once or twice a year) the money can sit in the escrow account for more than six months. Or even longer.

It can be crazy making, but with good systems in place, it works.

So, how does the system break down? This is the other thing a lot of authors have been asking, so I’ll go through some scenarios.

Mind you, there are thousands of scenarios, but I’ll pick the ones I’ve seen most since I started publishing in 2003.

- The market shifts.

So, this is the one that happened to Torquere in 2009. From 2003 when we started, to early 2009, almost all of TQ’s sales were on site, or direct. Literally 90%. In a direct sale, if the publisher is charging $5.99 for a book, then if the author gets 50%, about $2.99 goes into escrow. The other 2.99, less the credit card or Paypal fees, goes to the general fund. On a distributor site, like Amazon, if the book sells for $5.99, Amazon keeps 1.79. The author and publisher then split the remaining $4.20. In early 2009, the market shifted on us, and suddenly, 95% of our sales were going through distributors like Amazon, Fictionwise (which was bought by B&N), All Romance Ebooks, etc.

Just like that, we lost a huge chunk of our operating budget. Added to that, we were suddenly getting paid for the bulk of our sales on a 60-90 day lag instead of instantly.

This was the year we had already committed to Romantic Times in Orlando, with 2 sponsored parties, a rental house, seven employees and authors attending. To say the least, we were over-committed until the distributor payments started coming in for the big rush of sales now happening on the distributor sites. I was also paying royalties out of a rental house in Orlando, and losing my mind.

This is when it would have been tempting to borrow from the author escrow, since a lot of that money wouldn’t even be reported to the authors for another 3-6 months.

Instead, we took out a home equity loan to pay operating costs, and went without our author royalties and salaries for nearly three months to make sure everyone else got paid.

2. Expanding or advertising to add to the market

This is what I’ll call the All Romance Ebooks or Ellora’s Cave example.

Ebook sales have been a boom and bust proposition. For the most part, we’ve seen boom. There are times when market growth is enormous. When that happens, businesses tend to invest in new technologies or processes. Ellora’s Cave, for instance, invested in what I’ll call large scale marketing. They bought a bus. They did cons. They took out major ads in big magazines. Which was great, but when the next market shift happened, and they were over-committed, like I mentioned with TQ above, they dipped into the author escrow fund, even as they started selling off assets and cancelling commitments. I know a lot of folks will say EC is not a good example, because by the end, they were pretty nefarious, but to begin with, it was a matter of trying to cover debts. They were taking money from one account to make another look up to date, which is a practice called teeming and lading. All Romance E books has the same sad tale. They were a distributor (Torquere was their very first client) and as the e book romance market boomed, they invested thousands of dollars into becoming a publisher too, hiring more staff and spending enormous amounts of money on advertising and production. Unfortunately, they found out there was less money in publishing due to the costs of doing business. Again, I don’t think ARE wanted to do anything nefarious to begin with. In fact, rumor has it, Lori James thought she had a buyer for the business, and she would have paid her debts with that money, but by then it was too late. She’d spent money that wasn’t hers, and wasn’t able or willing to personally make good on it.

3. This is the Silver/Venus Press/Ebookad model

Take everyone’s money and leave the country. Yeah. This is not the system breaking down, and this is the worst case scenario. Grr.

There are a million other things that can happen, or as our accountant, a 75 year old Texan who had never even met a gay person before me, said, “Publishing is the most complicated business I’ve ever encountered.”

Anyway, I hope that helps everyone understand better how publishing does, and sometimes doesn’t, work. All rights based businesses such as publishing, song-writing, art, photography and so on can have these kinds of issues, but it comes down to the fact that once that money is earned, it belongs to the artist. Then it’s up to the publisher to get it to them.

XXOO

Julia